Until last year, only one woman had been awarded the Nobel Prize for Economics. Among Elinor Ostrom‘s several merits, she overturned a widely held view in academic circles, namely that the collective use of natural resources leads to their inexorable destruction. Ostrom’s turning point is rooted in the testimony of age-old customs, and one example belongs to the region of Trentino, Italy.

The tragedy of the commons

Think of a fishing basin, a resource freely accessible to anyone endowed with a boat and nets, and therefore difficult to protect with barriers of any kind. We can foresee that many people will be tempted to exceed the individual quota of fish that would guarantee the sustainability of the shoals. Safeguarding tomorrow’s fisheries requires everyone’s cooperation, yet everyone has the opportunity to continue fishing undisturbed, benefiting from the restraint of others while avoiding limits on their own consumption. It is easy to see that one of the foreseeable outcomes is depletion – extinction.

Ostrom’s thesis is that this is not an inevitable fate. In perhaps her best-known book, Governing the Commons, she illustrates the case of two villages at opposite ends of the geographical spectrum – Törbel, Switzerland, and Hirano, Japan. Both have shared the collective management of forests and pastures for centuries, thus preventing the tragedy of the commons from crushing their destinies. Their success can be traced back to rules adopted by organisations as diverse as the collective control of irrigation canals in Valencia, or the preservation of watersheds in California.

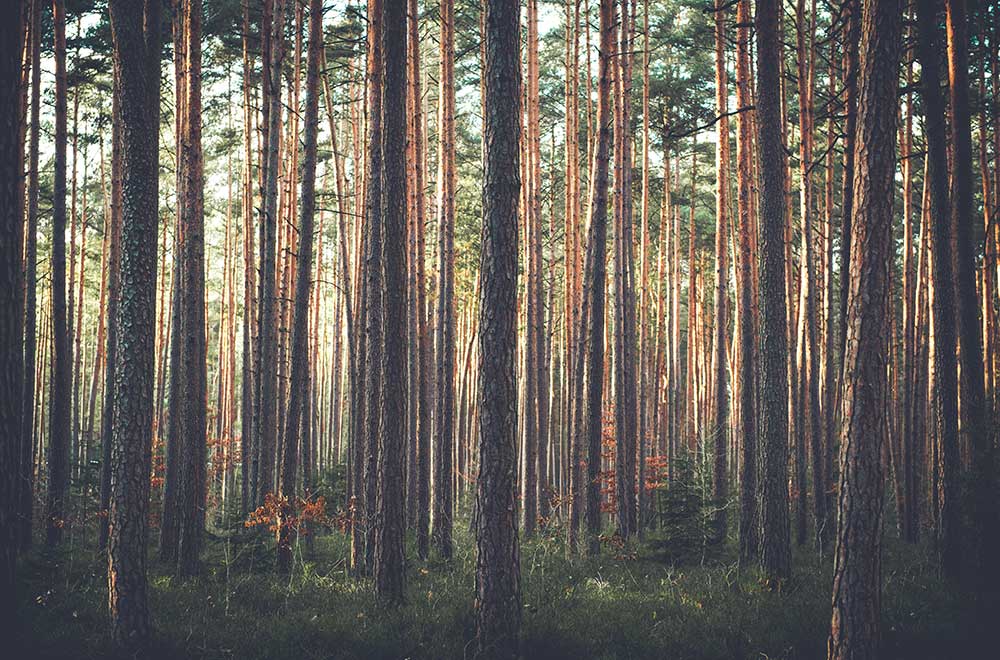

It may come as a surprise, but Trentino has resorted to remarkably similar systems, codifying procedures for the management of the forest heritage since the 13th century, thereby preventing its over-exploitation.

This article is a brief praise of those ancient traditions, the spirit of which still guides local associations that join us in the planting of new trees.

The administration of Alpine forests in the Middle Ages

The peculiar historical events that we are about to recount have been projected onto the international scene by Marco Casari, professor of Economic Policy at the University of Bologna. The following is a summary of an article of his, to which we refer the most engaged reader.

Since we are going to focus on forest management, it is worth remembering that until not too long ago, wood was a particularly precious resource. It served as a source of fuel, a building material and a commodity. The communities therefore had to cope with internal pressures for the excessive use of timber, as well as theft from other communities.

In Trentino, each local community developed informal rules to manage common economic resources. Despite this, outsiders still constituted a danger, since there was no higher authority to whom disputes between valley dwellers could be addressed. A further disadvantage of the system was its inability to aggregate information for the benefit of the whole community, which made it more difficult to catch offenders or justify their conviction. From the 13th century onwards, some communities began to adopt so-called Carte di Regola, charters that codified and improved upon the set of informal rules.

The principles of sustainable management

What did the charters actually provide for? First of all, they formally excluded outsiders from making use of the commons: the administration of internal disputes became independent of the central Episcopal authority located in Trento, while it continued to act as guarantor for the application of charters among distinct communities.

The charters enshrined the commonality of decision-making through an assembly and elected representatives; it further established a system of supervision and dispute resolution, and included a common register to preserve the collective memory. Supervision was carried out by guardians, who had the power to fine offenders and personally collect part of the penalty.

These rules overlap exactly with the eight principles outlined by Ostrom for the sustainable management of common resources. By encouraging mutual monitoring and instilling a sense of common participation through collective deliberation, this particular set of incentives has enabled small communities to make balanced use of their common resources over the centuries.

The challenge of the commons for the 21st century

Abolished by Napoleon in 1805, the charters are a legacy from which we indirectly continue to benefit. These institutions stem from slow and inescapable research, and teach us to have the preservation of the territory at our hearts. External conditions have changed, and the grounds for the charters have largely disappeared – but not the principles underpinning them, which must inspire us if we are to continue caring for our common heritage.

As complexity and interconnectedness have merged the destiny of multiple communities in ever larger bodies, critical issues in the management of the commons have become more serious. The mechanisms that have been proved successful in preserving our natural heritage are now showing their inadequacy: social liquidity is loosening the possibility of mutual control, multiplying short-term actions. The protection of the ecosystem requires modern solutions, yet looking back at our history can be of encouragement, for men have already been able to respond to the formidable task of living together.