The upheavals of 2020 have accelerated the changing pace at which we live and create new products and services.

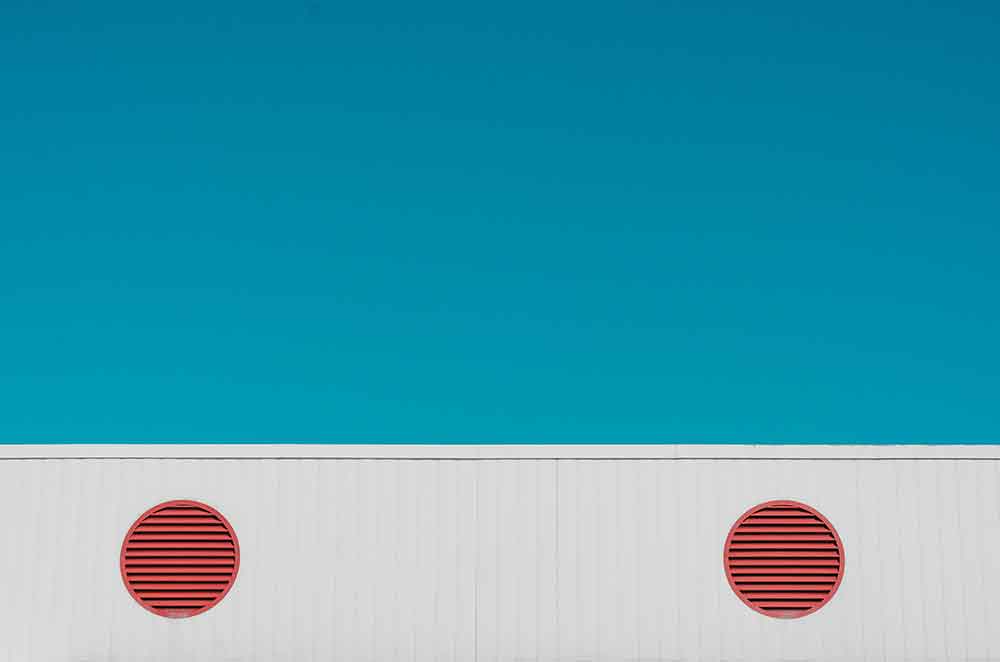

In the background, stand two simple geometric figures. The line characterises supply chains that start with the extraction of virgin materials, and which ultimately see the product as waste. The circle accompanies the thought that every output of one production process is the potential input of another.

The move from the line to the circle is undoubtedly among the greatest challenges of the 21st century. Every worthy environmental proposal today asks how to facilitate this transition. The European Circular Economy Action Plan, for example, is one of the main pieces of the new agenda for environmental sustainability promoted by the European Commission.

In this article, we will explore more closely these two paradigms, and the innovative solutions that have emerged from several sectors to meet the challenge of a future that is less dependent on raw materials.

The status quo: a linear economy

Whether you are reading these words from a smartphone, a computer or a tablet, you probably have a product of linear design in your hands. The materials used to assemble it are used for the first time, and their final destination, once the immediate life cycle of the device is over, will be solid waste (or e-waste at best).

The linearity of a production system is characterised by its narrowness in conceiving the use and purpose of a given product. Items are designed with the primary objective of winning the consideration of the end consumer, neglecting what will happen after their use. One of the major obstacles to increasing the effectiveness of plastics recycling, for example, is the excessive diversity of the polymers used, which are customised if only for aesthetic reasons. Such differences increase the cost of reuse and reduce the quality of the recycled product.

We can summarise the characteristics of the line in three words: “take, make, waste“. Take resources from the environment, make the desired item, discard at the end of its use.

Injections of circularity

The term ‘circular economy’ is an umbrella under which several concepts are collected: recycling, zero waste, upcycling, reuse.

Recycling has been perhaps the first strategy to be fully incorporated into national and European environmental policies. Back in 1975, the European Economic Community imposed the first standards on waste collection and recycling. However, the recycling paradigm has suffered its most severe setback on plastics. The most recent Pew report on plastic pollution prevention highlighted once again how recycling would not stop 18 million tonnes of plastic from flowing into the ocean by 2040, 65 percent more than 2016 levels. Among other things, recycling projects have rarely met the targets declared by their promoters.

The zero waste approach focuses on reducing the amount of waste produced as much as possible. It is a commitment to responsible consumption, which is active in bulk shops, solidarity purchasing groups and self-production. Achieving this objective is often combined with incentives to reuse and repair. One of the most innovative platforms in this field, Ifixit, has drawn up a ranking of smartphone repairability, an essential feature to ensure a longer product life.

Moving away from reuse and second-hand practices, upcycling engages creativity to twist the original use of the repurposed object or material: so a set of kitchen sinks can be transformed into a rotating partition wall, and an old snowboard into fashionable eyewear. Sounds familiar?

Completing the circle

An entirely circular process radiates from the centrality of design. As Simone Simonelli, our guest at VAIA Day 2020, pointed out, design has moved from forms to strategy, playing an increasingly important role in the process of product and service development.

It is no coincidence that the Ellen MacArthur Foundation, undisputed leader for the transition to a circular economy, defines the latter as “based on the principles of designing out waste and pollution, keeping products and materials in use, and regenerating natural systems”.

The difference between a linear and a circular process ultimately lies in the degree of responsibility that the company takes for the product’s life cycle: if it ends with the sale, the disconnection between the creator and the created is immediate, and the cost of disposal falls on society (or more often, directly on the environment).

Applications of the circular model are more likely to be found for objects. Among the examples that best illustrate the integral approach to a “round” design, Cyclon is the running shoe made of castor beans, and is replaced cyclically by the company itself. The design of the shoe has been optimised to minimise waste and is 100% renewable.

Cyclon is actually a service: regular deliveries are backed by monthly membership, and the user does not own the shoe directly. A few years ago, architect Thomas Rau told Phillips that he wasn’t interested in buying a lighting system, he just wanted to have the “right light”. Thus was born the “Pay per Lux” model, which perpetuates the reuse of used materials in a closed loop. Bosch’s BlueMovement initiative is a further example of the circularisation of processes through the provision of a service.

A question of incentives…

It will not have escaped the attentive and curious reader that Rau, Phillips, and BlueMovement have one thing in common: they are based in the Netherlands. Of course, among the case studies of circular economy catalogued by the Ellen MacArthur Foundation we find initiatives scattered all over the world, but among the pioneers of modular furniture is Ahrend, and the first model of modular headphones on the market is produced by Gerrard St. Where are both HQs located? Amsterdam.

This is no accident. The Dutch government has promoted a particularly ambitious transition plan, with the aim of reducing raw material consumption by 50% by 2030 and moving to a waste-free economy by 2050. To achieve this, the Netherlands has introduced shared producer responsibility for waste management in the electronics and automotive sectors and plans to extend this to other sectors soon. Other measures include market incentives, specific guidelines and targeted legislative action.

Working on the current incentive system is a challenging path, given the multiple interests at stake. One of the most radical proposals (made as early as 1976) is to increase taxation on raw materials to the benefit of lower taxes on labour, benefiting the labour-intensive processes that often characterise circular production models. Softer approaches favour instead the creation of more stringent European standards in order to create a uniform market capable of influencing value chains worldwide.

…and of right ecosystems

If there was a period in history that highlighted the global interconnectedness of production systems more than ever before, it is the one we are currently experiencing. The transition from line to circle depends critically on international collaboration, and may be the most frustrating realisation, given the perennially unripe fruits borne by the fight against climate change.

In Europe, the countries most committed to the transition act as drivers for the whole Union. They are aware that achieving their targets means producing a general alignment between Member States, so as to avoid dangerous races to the bottom to attract the production of goods and services. The lack of specific standards and effective guidelines is to date, together with objective technical impossibilities of reprocessing specific materials of high practical use, one of the biggest obstacles on the road to a more circular economy.

In the primitive economy described by Marshall Sahlins, an indigenous man received a knife as a gift after having run to the aid of a missionary; it soon began to circulate within the tribe, since keeping such a precious object for oneself would have triggered a destabilising game of personal envy.

That circularity was inherent in many practices, and endured in Indo-European philosophical systems as far back as 2500 years ago. What is the shape of ancient thought?, wondered Thomas McEvilley in a crucial collection of essays. Round, he concluded simply and disarmingly. Having (momentarily) escaped the Malthusian trap, returning to that original form now requires a conscious effort on our part. Folding the line into a circle, bringing the two ends as close as possible: that is the work that lies ahead.